Saudi Retina Group

News and Events

12

Jan

For the past 26 years, board certified ophthalmologist and fellowship trained retina surgeon Dr. C. Armitage Harper has been driving to hospitals from Georgetown to San Antonio to focus on one kind of patient: our smallest, most vulnerable babies who may have Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP). ROP is an eye disorder in babies born before 32 weeks that can lead to lifelong visual impairment and blindness.

Dr. Harper’s passion for saving babies from blindness was recently featured in an article by Nicole Villalpando in the Austin American Statesman. You can read the entire article below or find it on the Austin American Statesman website here.

Dr. C. Armitage Harper gazes into the tiny eye of a premature baby in the neonatal intensive care unit at St. David's North Austin Medical Center.

He's looking for signs of change. Catch problems quickly and the baby will grow up with

almost normal vision. Find them too late or not look at all, and risk a lifetime of blindness.

Harper is one of about 40 doctors in the world who specializes in retinopathy of

prematurity, a disease that happens when the blood vessels in the retina grow abnormally.

It typically happens in babies who are born before 32 weeks gestation and weighing less

than 3 pounds.

The oxygen they receive in their isolettes plays a factor. Give them too much and you risk

damaging their eyes, but it's a delicate balance because these babies need the oxygen to

survive until their lungs are fully developed.

Every week, Harper takes his knowledge and skill to hospitals up and down Interstate 35.

Before the pandemic, he also was traveling to other countries to help doctors prevent

blindness through both the nonprofit organization Orbis and its Flying Eye hospital and his own nonprofit Small World Vision.

Harper is highly respected even among the retinopathy of prematurity specialists and

academics, says Dr. David Breed, the medical director of the NICU at St. David's Women's

Center of Texas inside North Austin Medical Center, who has worked with Harper for

decades and been with him at conferences.

"When Armie speaks, they listen," Breed says.

A promise made and kept

Harper, 59, is the third of four Clio Armitage Harpers. His father was an

obstetrician/gynecologist. His father's grandfather was also a doctor and a chief of

ophthalmology. There were also writers in the family, including the original Clio Harper,

who was the publisher of the Arkansas Gazette.

When Harper was living in Tulsa as a boy, his dad took him to work for three nights in a

row during which he watched the happiness of babies being born. Then his dad sent him to

neighbor Dr. Bill Simcoe, who was a world-renowned ophthalmologist.

"I loved microsurgery," Harper says he realized.

After graduating from St. Stephen's Episcopal High School in Austin, Harper headed to

Vanderbilt University and then to the University of Oklahoma for medical school.

During his residency at Charity Hospital, Louisiana State University, in New Orleans,

Harper made a promise. His wife, Ruthie, also a doctor, was pregnant with their daughter

Holly and began having preterm labor at 18 weeks. Ruthie Harper made it to 34 weeks

gestation with Holly. During that time of uncertainty, Armie Harper made

this promise: "If they came out OK, I would do babies for the rest of my life," Harper says.

That's where it all started.

Holly Harper did make it OK. At 28, she just graduated from medical school at Vanderbilt

and is doing a residency in pediatrics at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Son Clio, 26, the fourth Clio Armitage Harper, has a degree in applied math from

University of Southern California and is in the Marines and training to fly F-35 jets.

Harper made good on his promise to take care of babies. After five years in New Orleans,

he headed to Casey Eye Institute at the University of Oregon in Portland. There he

received training in caring for retinas of all ages, including retinopathy of prematurity.

He moved to Austin and joined Austin Retina Associates in 1995. About 80 percent of his

work is in retina problems in adults because it's much more common to have a problem as

you age.

The other 20 percent is the kids he's watching carefully and then treating before they go

blind. Treating children is much more difficult because of their size and because it has to last,

Harper says.

An adult patient who is 80 years old might experience a couple of decades of changed

vision.

"When we fix a child it's 80 years that we have to be able to influence," he says. "It's 80

years of vision."

Getting ophthalmologists to go into eye diseases of the youngest patients is tricky.

"People don't like kids," Harper says. "They are hard to examine. You can't ask them 'What

do you see?'"

Harper has to understand the minute differences in the retina to know whether its going to

cause future problems or not.

As Austin grows

Last year, Austin Retina Associates screened 550 babies in NICUs from Round Rock to San Antonio. On one recent Sunday, Harper screened 14 babies at St. David's North Austin, 11 at Dell Children's and 15 in San Antonio.

He likes to see babies on Sunday because there's less traffic, making the drive between

hospitals easier, but he'll return whenever there's a baby who needs to be seen again.

In the United States, more and more babies are surviving after being born as micro

preemies.

"We're saving babies now that previously did not have a chance," Breed says. "We're

sending home babies with good outcomes that 25 years ago would have died."

These micro preemies are at risk for infections, head bleeds and lung disease. In their eyes,

the retina is only 50% developed, Harper says.

Babies born at such early gestations need a lot of oxygen, but too much oxygen can impact

the heart and lungs as well as the eyes farther down the road. "It's a double-edge sword,"

Breed says.

They are learning, and Harper is helping to guide them with research and getting NICU

patients enrolled in studies for new medications and techniques. "We're getting better at

what we do," Breed says. "We do have some kids that have been micro preemies that had

eye disease and do not have glasses."

When Harper arrives in the NICU, he takes a cart with all of his supplies from isolette to

isolette. He looks in the back of an eye and tells his assistant what he sees. "He's very

quick," Breed says. "It minimizes the discomfort for the baby."

Then Harper comes by and tells the nurses and doctors which patients he's worried about.

"He can spot a kid weeks ahead of time" who will have more issues, Breed says.

As Central Texas has grown and filled its NICUs with babies, Harper's job has grown. He

now has a partner, Dr. Ryan Young, who also shares his specialty.

A fellow retinopathy of prematurity specialist who was training Young in Miami reached

out to Harper, who was told: "I know you need help. I trained him, and you will hire him."

Harper is also doing training of his own as a consultant at University of Texas Health

Science Center in San Antonio and at University Hospital in San Antonio, where he's

teaching residents about retinopathy of prematurity.

Watching medicine grow

Harper has watched the science in this field evolve immensely. At first, doctors

would freeze the outside walls of a retina to stop abnormal growth.

Then Japanese researchers developed lasers to stop the growth. That's what Harper had in

his arsenal when he was in training.

"You may be destroying a third of the retina," Harper says. It left a generation of

prematurely born children with a reduced field of vision and incredibly nearsighted.

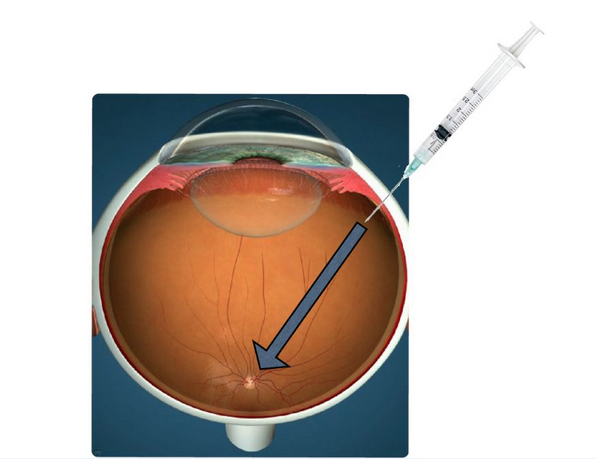

Now Harper is able through research studies to inject the eye with anti-vascular

endothelial growth factor or anti-VEGF medications. He is able to save peripheral vision.

Anti-VEGF medications allow doctors to delay laser treatment by targeting the protein

causing the excess growth. When babies reach 60 weeks (gestation plus chronological

age), lasers also can be used to make sure there won't be any abnormal growth, but those

lasers are used to a lesser degree to preserve more peripheral vision and to not cause

nearsightedness.

More innovation is on the horizon. "The future is genetics," Harper says. That could mean

injecting the eyeball to change the DNA to create cures.

In the case of retinopathy of prematurity, innovation also could come with better

prevention of premature birth.

When Quin Aldredge was born at 25 weeks gestation in 2000, he weighed 1 pound 2

ounces. His twin sister, Josephine, weighed 1 pound 8 ounces. His father's wedding ring fit

over Quin's shoulders.

Josephine had mild retinopathy of prematurity, which resolved on its own, but Quin's

retina was almost detached, says Quin's mother Tenley Aldredge.

"One thing about Dr. Harper, he's so calm, he's so reassuring, he's so evidently confident.

He's brave," Tenley Aldredge says. She remembers him coming into the room to explain

the surgery needed to save Quin's eyesight. "He comes in with such expertise and

calmness."

Quin knows that his peripheral vision was compromised because they didn't yet have the

anti-VEGF medication, but he says, without Harper, "I probably would have gone blind.

I'm so lucky I ended up with Dr. Harper and that's how things worked out. I feel like if he

hadn't been there, I would have ended up in a very different situation."

Amy Lambert's daughter, Catherine, was born at 25 weeks weighing 1 pound 7 ounces in

2014. "Her eyes were still fused shut," Lambert says. "For the first 21/2 months, we were

like 'keep the baby alive,'" she says. They had tried 10 rounds of in vitro fertilization and

had five miscarriages before becoming pregnant with Catherine.

Harper watched Catherine's eyes until it became clear they needed to do something. She

was injected with anti-VEGF medication as part of a research study, and about a year after

she left the NICU, she had laser surgery.

Now, Lambert says, Catherine's vision "is dramatically better than mine. Her eyes are

incredible." Because of the anti-VEGF, combined with the laser later on, Catherine has no

peripheral vision loss.

Lambert remembers the phone call from Harper on the day Catherine's eyes needed

interventions.

"He's just exceptional," Lambert says. "He just was making sure the parent was confident

and comfortable, but he was being very direct and real about what the situation is. He's

was very compassionate, but also this is the reality and this is what we need to do."

Harper follows all his patients at least yearly, and Lambert says he cares about all aspects

of Catherine's life and health and wants to know what her successes are.

A global problem

Harper did work with Vanderbilt in Haiti and with Orbis in China, and in 2016, he started

his Small World Vision nonprofit.

"I knew I wanted to do something to give back to the world and teach what I knew after

doing it for 20 years," he says.

In the United States, about 1,000 babies a year go blind because of retinopathy of

prematurity, Harper says, but not in Central Texas because of access to care.

In some parts of the world, retinopathy of prematurity accounts for 40% of blindness, yet

it's one of the most preventable causes of blindness.

When a friend wrote a paper about a NICU north of Mexico City that had a 40% rate of

blindness, Harper called that friend and started talking about oxygen saturation rates.

In the U.S. premature babies in NICU units have a blender that mixes ambient air and

oxygen to lower the oxygen saturation level. It helps preserve the eyes. The blender is a

$2,200 part.

Harper weighs the cost of a $2,200 part versus the economic cost of a blind child in a

developing country who cannot help his family.

There are homes all over Central and South America with blind kids in them with ROP,

he says.

It's not just the ROP that could be prevented with oxygen blenders. Lung diseases

and head bleeds come out of babies being hyper oxygenated, he says.

Small World Vision was born when he traveled to Mexico with oxygen blenders carried in

scuba bags.

He wants to create self-contained NICU units that would have all the things a modern

NICU needs, including the blenders, which he could bring to places that need them. Along

the way, it's about educating, while listening, about the importance of not hyper

oxygenating babies.

"There is some resistance to change," he says. "You have to be gentle, you can't be a knowit-

all heavy-handed American."

For his Central Texas colleagues, though, the respect for his knowledge is there.

"I truly feel we're so lucky to have someone of his caliber," Breed says. Harper not only

treats Breed's patients, he's treated Breed's father for a retina issue and some of his

colleagues.

"He's that good, that highly respected," Breed says.

For Harper, the work is interesting and full of innovation. It's also rewarding because it's

about kids.

It's a passion," he says. "You watch them grow ... you've made a difference in their lives.

Read Details